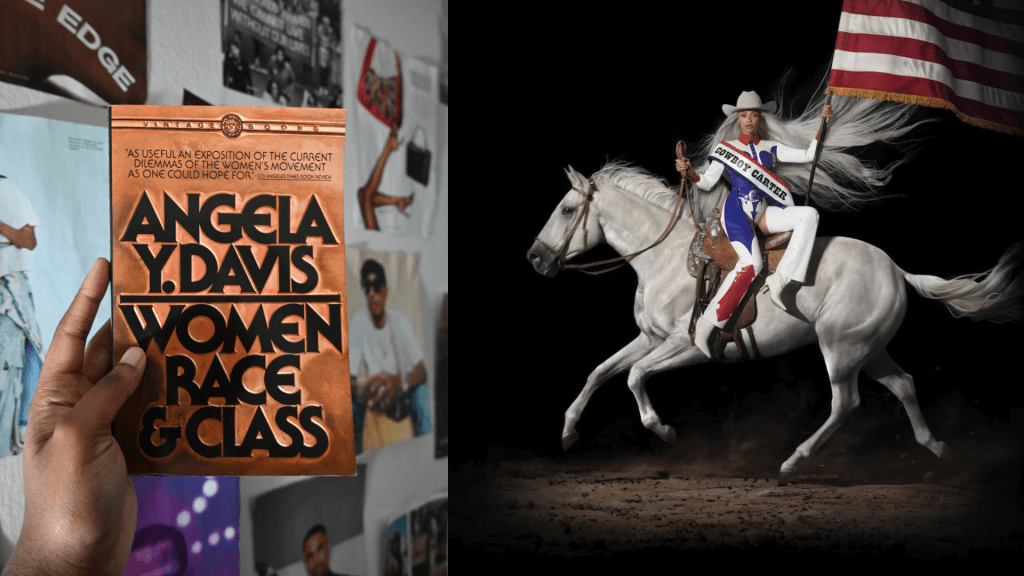

After two weeks, I finally finished Women, Race, & Class last night! It was a slow read for me as I was finishing my Gendered Communication class and wanted to enjoy Spring Break. Given what I study, it can be hard for me to read book on history or theory that doesn’t relate to my research, but I felt ready to read this when I picked it up. I’ve read Are Prisons Obsolete and Freedom is a Constant Struggle by Angela Davis in the past and expected this to be more theoretical, but was surprised, and happy, to get a history lesson instead.

Published in 1983, this book is a collection of essays that give an intersectional analysis of the women’s movement in the United States and pays special attention to race and class. Each chapter touches on specific moments in history regarding womanhood, anti-slavery, suffrage, education, emancipation, unionization, the club movement, the Communist Party, sexual violence, reproductive rights, and the working class. Davis highlights the stories we don’t always hear about when learning women’s history. She shows the very unique position Black women continuously exist in pertaining to women’s rights movements, but also how Black women have been uniquely situated to aid in capitalist gains of the ruling class.

This book will hold a special place in my heart (and on my bookshelf) for a number of reasons. Before I started grad school, I sometimes questioned why I have always been concerned with issues of race but not gender. It wasn’t as if I denied the presence of gendered oppression, but you’d likely never hear me call myself a feminist. It wasn’t until I read Black Feminist Thought by Patricia Hill Collins that I saw how and why being a Black woman in America comes with a certain history that I never saw articulated in mainstream (read white) feminist movements.

Women, Race, & Class does the same thing for me, less from a theoretical standpoint, but by historically showing how Black women in America have more or less felt how I’d always felt. That either the outright racism or indifference to the plight of Black women in the U.S. in white feminist spaces sometimes necessitates that we organize separately to address our concerns.

“It was those women who passed on their nominally free descendants a legacy of hard work, perseverance and self-reliance, a legacy of tenacity, resistance and insistence on sexual equality—in short, a legacy spelling out standards for a new womanhood.” (29)

Women, Race, & Class by Angela Davis (1983)

It also made me very aware of the white women who were phenomenal allies to Black women and the movement for Black Liberation — from abolition onward. So why is it that I grew up learning how pivotal of a role Susan B. Anthony played for the rights of (white) women, but not how she co-opted white supremacy in order to do so? Why did I never learn about the countless white women who were in community with Black women? the ones who recognize that all oppression is connected and to be in solidarity with each other helps us all? This book has reshaped my view of feminist movements a bit more in understanding that what I learned growing up is skewed and comes from the perspective of the ruling class (i.e. middle-class, white women).

So, I naturally begin to think about storytelling, the preservation of history, and which stories are told as American history.

When Beyoncé released the COWBOY CARTER album cover, there were a number of critiques about her holding up the American flag (albeit, the entire flag is not pictured). As one of the least patriotic/anti-American person I know, I wasn’t that upset as other people were.

There is so much validity in critiquing any nation-state (especially the U.S. and its numerous imperialist, colonialist, capitalist, and racist projects) as well as the portrayal of a flag as the visual representation of a nation-state.

patriot (n.) a person who vigorously supports their country and is prepared to defend it against enemies or detractors

At the same time, I do understand that some people’s displays of patriotism (or perceived patriotism) is less rooted in co-opting oppression, but more about cultural pride. And for Black people in America that is (sometimes) where our patriotism comes from. Reading Women, Race and, Class shows how Black Americans have historically done physical, mental, and emotional labor in an attempt to shape this nation into something worthwhile (see abolition, suffrage, education, etc.). We’ve continuously worked to make the future of this country better than the way it has been given to us. Sure hindsight is 20/20 and there is still a long list of political, economic, and social issues. (The abolition of slavery led way to the prison industrial complex. We’re still dealing with voter suppression. Access to quality education is largely dependent on wealth.) Despite this fact, the activism of Black Americans to improve the material conditions of slavery (pre- and post-abolition) shouldn’t go in vain. And quite frankly that kind of work should come with right to be a little patriotic.

There are also a few instances where Davis points out how popular media either shapes or further reifies harmful stereotypes of Black women. Studying media & representation, I do feel that the creators of our time hold some social responsibility to rewrite stereotypes, or at the very least not perpetuate them. Whether or not you believe Beyoncé gets it right when it comes to representation, it’s hard to deny that her art doesn’t start critical conversations. This might be the most in depth I’ve seen people talk about the origins of country music outside of the Intro to African American Music class I took during undergrad. As a continuation of work songs, negro spirituals, and the blues, country music birthed out of Black musical tradition is deeply tied to our politics & social justice in many ways.

I will say, my appreciation of Beyoncé and her artistry is less about creating a god out of her or putting her above reproach (although it is humorous watching and engaging in/with people who do). It’s more about seeing how, given her status, she’s able to start or continue conversations about (Black/American) history, culture, and art.

I can’t, of course, ignore the complications of her and her billionaire husband. Women, Race, and Class ends in the middle of a history regarding housework, industrial capitalism, and labor in general. Despite recent convos about trad wives, society has largely moved past the necessity of a housewife as more women enter the workforce, which Davis does point out how this was (and still is) being exploited by capitalists. In a capitalist society, our labor is inherently capitalist and, yes, creative labor is labor. I can’t/won’t speak to the way Mrs. and Mr. Beyoncé have obtained their wealth through business because my attention to the two of them starts and stops at their careers in the music and entertainment industry.

I will say that capitalism did not start with The Carters (regardless of what Jay Z says) and it likely won’t end with them either. Dismantling capitalism (or any oppressive system) requires a collective effort that each one of us needs to be involved in and it will look different based on who you are. For some of you, it may very well mean calling out Mrs. and Mr. Beyoncé on the loads of wealth they’ve accumulated. For others it’s divesting from large corporations & reinvesting in local economies or living on a self-sufficient farm with friends and family.

Beyoncé does hold this strange position given there’s no such thing as an ethical billionaire, but simultaneously holds enough cultural weight that creating a country album would cause this many of us to discuss how Black Americans, in the face of institutionalized racist violence, simultaneously shaped American culture. So, do the monumental contributions of Black Americans warrant us (not me though lol) to be a bit patriotic? Or at least embrace how integrated we are in the fabric of this nation?

“My family live and died in America. Good ole USA Whole lotta red in that white and blue. History can’t be erased.”

YA YA by Beyoncé (2024)

Whether you’re reading Angela Davis or listening to Beyoncé (or, like me, doing both), we should never stop asking questions about what we’re engaging in. How does this challenge what I thought to be true? What is this teaching me about the/my world? How can I use what I’m learning to be better? Who is still missing, where can I find them, and how do they fit in the larger picture?

Leave a reply to (an incomplete) reading list 4 liberation – shay the student Cancel reply